The evil fairy’s costume from Nureyev’s « Sleeping Beauty, » trapped in a glass case. Her dancer spirit roamed the halls of the Palais Garnier.

20 danseurs pour le XXe siècle. Palais Garnier. September 30th

The public spaces outside the auditorium of the Palais Garnier are designed for circulation, a bit of people-watching, but certainly not for strap-hanging.

I feared getting around Boris Charmatz’s seemingly random collage of dance and dancers would feel like being stuck in the Paris metro. God, another accordionist. You rush to the car behind, but then get your nose crushed against the door. Moments later you find yourself waist-high in a school group. Then, abruptly, it all thins out and you are gawking at two boys rapping and doing back-flips in the aisle. Maybe, with luck, you get to sit.

That’s why I only took one chance on 20 Danseurs pour le XXe siècle as adapted for the Paris Opéra dancers. The Charmatz/Musée de la danse concept sounded borrowed from what has, in the space of twenty years, become a theatrical staple. Actors spread out throughout an a-typical space repeat scenes – fragments of a story – and are gawked at. You use your legs to trace a path, choose how long you want to stand in one doorway, and worry about what’s going on elsewhere. Chances are you will construct a narrative that makes sense to you, or not. I find this genre as annoying as where — just when you start to get into the novel you are eaves-reading – your seatmate hops off at her stop.

I was so wrong. Instead of a half-overheard conversation in a noisy train, here we were treated to an anthology of coherent one-page short stories. It was the hop-on-hop-off tour bus: only a three-day ticket lets you get to enough of the sights. But even one day in Paris is definitely worth the trip.

If, as Fred Astaire’s Guy Holden says, “chance is the fool’s name for fate,”* somehow I was fated (pushed and pulled?) to stopping off at those stations that housed tiny but complete narratives of sorrow. (A Balletonaut has told me I missed much happy, even foolish, fun. Next time, I’m travelling with him).

“How do you do? I am delightful”*

Perhaps the oddest thing for both conductor and passengers is finding themselves face to face. When the lights are out in a theater, the auditorium looks like a deep dark tunnel from the stage…not like these hundreds of beady eyes now within touching distance. And even we were uneasy: one wall had been broken down, but where to put eye contact? We did what we usually do at the end of each snippet: applauded and moved on. Very few dared to actually approach and speak to the ferociously focused dancers. Thank god joining in some kind of conga-line was not part of the plan. Instead:

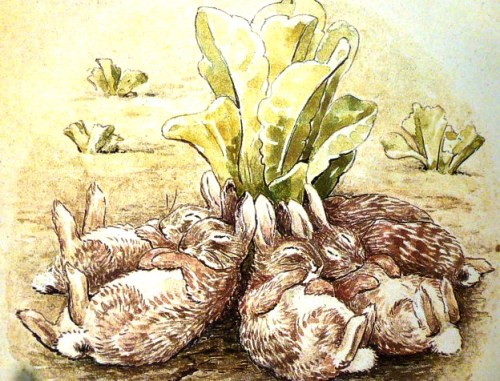

I stumbled across Stephanie Romberg, loose and intense, unleashing all of Carabosse’s furious curse within the tiny rotunda of the “Salon du soleil.” As in each case here: no set, no costume. It felt almost obscene to be peeping at a body sculpting such purely distilled rage. Think: the crazy lady, with a whiff of having once been a grande dame, howling to herself while dangerously near the edge of the subway platform.

Myriam Kamionka’s luminous face and warm and welcoming persona then drew me over into a crowded curving corridor. Casually seated on a prop bench in front of a loge door, she suddenly disappeared into the folds of Martha Graham’s Lamentations. I wound up experiencing this dance from total stage left. Pressed between tall people, my cheek crushed against the frilly jabot of Servandoni’s marble bust, I felt like someone pretending not to be looking directly at the person collapsed on the station floor. And then I couldn’t stop staring. You could almost feel the air thicken as Kamionka drew us into her condensation of despair. Even the kiddies, just a few feet away, sat silent and wide-eyed and utterly motionless. As they remained for the next story: a savagely wounded swan in pointes and stretch jeans dying, magnificently.

In search of air to clear my head I wound up behind two visions of Stravinsky’s Sacre. The view from the wrong end of the station, as it were, was so cool: this is the corps’ or the stagehands’ view!

In Pina Bausch’s version, Francesco Vantaggio pushed against the limits of the long and narrow Galerie du Glacier like a rocking runaway train. His muscular, dense, weighted, rounded and fully connected movement projected deep power, unloosed from the earth. When he repeated that typical Pina shape that’s kind of a G-clef – arms as if an “s” fell on its side (rather like an exploded 4th), body tilted off legs in passé en pliant – I thought, “man, Paul Taylor’s still alive. Get on the subway and go barge into his studio…now!” Yet when it was over, as he moved away and sat on the floor to the side to decompress and I was trying to catch my own breath back…I feared making eye-contact. (Forget about, like, just walking over and saying “Hi, loved it, man.” You don’t do that in Paris, neither above the ground nor underneath it).

Marion Gautier de Charnacé, on the outdoors terrace, then made the honking horns and sirens accompanying “The Chosen One’s” dance of death seem like part of the score. All our futile rushing about each day was rendered positively meaningless by the urgency of Nijinsky’s no-way-out vortex of relentless trembles and painful unending bounces. Even if she was wearing thick sneakers, I since have been worrying about this lovely light-boned girl repeatedly pounding her feet on a crushed stone surface over thirteen days. Make-believe sacrifice, yes. Shin-splints, no.

Finally I cast my eyes down from an avant-foyer balcony to spy upon Petroushka’s bitter lament of love and loss, as Samuel Murez – making it look as if his limbs were really attached by galvanized wires — let the great solo unfold on the Grand Escalier’s boxy turnabout. A moment of grace arrived. Two little girls framed within the opening to the orchestra level behind him could not resist trying to mirror his every movement. Not for us, but for themselves. As if they really believed he was a life-size puppet and were trying to invite him home to play. The barrier between audience and performer, between real and unreal, the prosaic and the magical, had finally given way. Too soon, it was all over. Time to wave goodbye.

“Chances are that fate is foolish.”*

Back on the metro the next morning, I got a seat and quietly began to concentrate on my thoughts. But then at the next station that woman got on who still gives us no choice but to endure three stops’ worth of “Besame mucho” whether we want it or not.

* Quotes are from Fred and Ginger’s 1934 The Gay Divorcée, especially as mangled by Erik Rhodes’s enchanting “Alberto Tonnetti”