A classical ballet, just like a classic book you’ve reread many – many ! – times, almost never fails to delight you again when you rediscover it. Here are some of my most recent ones at the Paris Opera ballet.

Hannah O’Neill and Germain Louvet: a most pleasant discovery

Don Quichotte on March 27th

Don Quichotte on March 27th

For a while now, I’d been unconvinced by the pairing of Hannah O’Neill with Hugo Marchand. His large presence overwhelmed her and their lines and musicality did not match. He made her look small and quite pallid, which is odd considering that the smaller Gilbert never did. Maybe it’s because Gilbert is clearly a fighter while O’Neill’s persona is more demure?

But who else could she dance with? Germain Louvet? Pairing them in Don Q on March 27th proved splendid: their lines and timing and reflexes completely in synch. They even giddily broke the line of their wrists exactly when the music went “tada.”

But Don Q is a comedy.

Up until now, for me, Germain Louvet only lacked one thing as an artist: gravitas. It was impossible to find fault with his open-hearted technique, but somehow I always got the feeling that he wasn’t quite convinced when he played a prince. Some part of him remained too much a stylish young democrat of our times.

His acting could reminded me of how you tried to keep a straight face when you got cast as Romeo at an all-girl’s high school. You tried really, really hard, but it just wasn’t you.

Germain Louvet (Basilio) et Hannah O’Neill (Kitri).

* *

Giselle. Saluts

Giselle on May 28th

Then something happened when Louvet stepped out on the stage on May 28th. Here was a man whose self-assurance seemed worldlier, tougher, critical distance gone. Within seconds in his pantomime with Wilfried, Louvet “was” that Old-World well-mannered man used to being obeyed and getting what he wants at any restaurant. I was convinced.

And it all came together when Hannah O’Neill answered his knock-knock. A healthy, normal girl with no secrets who has clearly been warned about men but who has decided – on some level to this Albrecht’s surprise – that he is a good man.

Everything about O’Neill’s Giselle, from her first solo onwards, breathed restraint and modesty. She was the kind of girl who speaks so softly you cannot help but lean in to her. Louvet’s Albrecht clearly felt this.

Once again, every little danced detail matched. But more than that, these two were literally inside the same mental space. Both of them reacted strongly to Berthe’s narrative: O’Neill spellbound and Louvet taking that cautionary tale personally, as if Giselle’s mother had just put a hex on him. Later, when Giselle shows him her big new diamond pendant, Louvet managed the degrees of that multileveled reaction of “I must not tell her she has a scorpion crawling on her chest just yet.” And none of this felt like he was trying to steal the spotlight. He was really in the moment, as was she.

Antonio Conforti’s Hilarion had also been believable all along, his mild state of panic at the growing romance evolving into fear for her life. (His Second Act panic will be equally believable). When Conforti had rushed in as if shot out of a cannon to put a stop to the romance, you could see how Giselle knew that he was no monster. This nice Giselle’s inability to disbelieve anyone made her mad scene all the more poignant. No chewing of the scenery, her scene’s discreet details once again made us want to lean in and listen. Giselle’s body and mind breaking down at the same time was reflected in the way O’Neill increasingly lost control, even the use, of her arms. She took me directly back to one awful day when I was crying so hard I couldn’t breathe and walked straight into a wall. Utter stunned silence in the auditorium.

Louvet’s differently shaped shock fit the character he had developed. You could absolutely believe in the astonishment of this well-bred man who had never even put one foot wrong at a reception, much less been accused of murder.

Woman, Please let me explain

I never meant to cause you sorrow or pain

So let me tell you again and again and againI love you, yeah-yeah

Now and forever*

In Act II, you had no need of binoculars to know that the regal Roxane Stojanov was the only possible Queen of the Wilis. Her dance filled the stage. Those tiny little bourrées travelled far and as if pulled by a string. She seemed to be movingNOTmoving. Her reaction at the end of the act to the church bells chiming dawn — a slow turn of the head in haughty disbelief — made it clear that this Queen’s anger at one man, all men, would never die. Clearly, she will be back in the forest glade tomorrow night, ready for more.

I was touched by the way Louvet’s Albrecht was not only mournful but frightened from the start. It’s too easy to walk out on the stage and say “just kill me already.” It’s another thing to walk out on the stage and say “I’ve never been so completly confused in my entire life.”

Woman, I can hardly express

My mixed emotions at my thoughtlessness

After all, I’m forever in your debt…*

Hannah O’Neill et Germain Louvet (curtain call)

* *

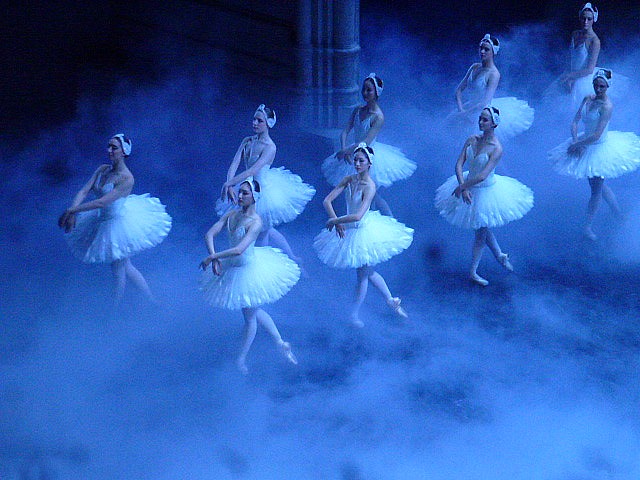

Le Lac des cygnes on June 27th

Le Lac des cygnes on June 27th

O’Neill’s unusual interpretation of Odette – under-swanned and unmannered – reminded me of Julia Roberts saying ,” “I’m just a girl standing in front of a boy asking him to love her.” No diva here. O’Neill’s swan/princess had not only been captured but promoted queen against her will. All she wants is to be seen as a normal girl. I think this take on the role might have put out some in the audience nourished by that awful horror movie’s over the top clichés. Once again I fell for the rich nuances in this ballerina’s demure and understated authority.

And here was Germain Louvet again! Elegant, well-mannered, gracious, and absolutely un-melancholy. His prince was not self-involved, yet regal with a kind of natural elegance that set him apart. I’ve met people like that.

Louvet’s at ease Siegfried just wants to dance around with his friends and has never thought much about the future. Often the Queen Mother scene just seems like an intertitle in a silent movie: basic information needed to make a plot point. The acting can be light, as in Paris the dancers cast as queen mothers are mostly ten to fifteen years younger than their sons. Young Margaux Gaudy-Talazac, however, had believable authority and presence. I cannot put my finger on exactly what she and Louvet did and when, but what developed was clearly the Freudian vision Nureyev had had for this ballet in the first place. “Why do you want me to go find a woman? I’m just fine here with you, mommy.” This Siegfried’s rejection of the Act Three princesses was preordained no matter what. What a pity, then, that Thomas Docquir’s flavourless Wolfgang and stiff Rothbart gave all the others little to work against.

Back to no matter what… But what if a woman unlike all other women actually exists? Hey, what if even dozens of them are lurking out there just outside the windows? Louvet’s tiny gesture, stopping to stroke a tutu as if to check it were for real as he progressed in through the hedgerow of swan maidens, made these thoughts come to life.

O’Neill and Louvet’s courtly encounters were like the water: no added ingredients, pure and liquid. O’Neill kept her hands simple – the way you actually do when you swim– and Louvet gently tried to get in close enough to take a sip but she kept slipping away from him. As he gently and with increasing confidence pushed down her arms into an embrace, you could sense that she couldn’t help but evaporate.

Their lines and timing matched once again. But I wondered if some in the audience didn’t find this delicately feminine and recognizably human Odette too low energy, not flappy enough? But she’s a figment of HIS imagination after all! This Siegfried was in no need of a hysteric and obviously desired someone calm, not fierce. [This brings me back to what doesn’t work in Marchand/O’Neill. He may appreciate her in the studio, but on stage he needs a dancer who resists him].

As Act Three took off, I found myself bemused by when I do focus, and when I don’t focus, on how this production’s Siegfried is dressed in bridal white. Louvet’s character was indeed both as annoyed and then as anguished as an adolescent. No other betrayed Siegfried in a long time has buried his face in his mother’s skirts with such fervor.

Nota Bene: All nights, in the czardas, the legs go too high. The energy goes up when it should push forward. This ancient Hungarian dance is not a cancan.

As Odile, O’Neill once again went for the subtle route. Her chimera played at re-enacting being as evanescent as water, now punctuated with little flicks of the wrist. Louvet reacted in the moment. “She’s acting strangely. Maybe I just didn’t have time last night to see this more swinging side to her?”

In Act Four, O’Neill’s Odette was no longer under a spell, just a girl who wants to be loved. No other Siegfried in a long time has dashed in with more speed and determination. As they wound and unwound against each other in their final pas de deux of doom I wondered whether I’d ever seen Louvet’s always lovely partnering be this protective. The only word for his partnering and persona: maternal.

It wasn’t a flashy performance, but I was moved to the core.

And woman

Hold me close to your heart

However distant, don’t keep us apart

After all, it is written in the stars**John Lennon, “Woman.” (1980)

Le Lac des cygnes. Hannah O’Neill (Odette/Odile) et Germain Louvet (Siegfried).

*

* *

Sae-Eun Park : I found her and then lost her again

Gisele May 17 Sae-Eun Park and Germain Louvet

During Giselle, what I’ve been looking for finally happened. Before my eyes Sae-Un Park evolved from being a dutiful baby ballerina into a mature artist. And her partner, Germain Louvet (again!) whom I’d often found to be a bit “lite” as far as drama with another goes, came to play a real part in this awakening.

During Giselle, what I’ve been looking for finally happened. Before my eyes Sae-Un Park evolved from being a dutiful baby ballerina into a mature artist. And her partner, Germain Louvet (again!) whom I’d often found to be a bit “lite” as far as drama with another goes, came to play a real part in this awakening.

But this was not the same Albrecht, to boot. From his first entrance and throughout his dialogues with Wilfried, words from an oldie began to dance around at the back of my brain:

Well, she was just seventeen

You know what I mean

And the way she looked

Was way beyond compare

So how could I dance with another

Ooh, when I saw her standing there?*

I almost didn’t recognize Park. All the former technical mastery was still in place but it suddenly began to breathe and flow in a manner I had not seen before. She came alive. All her movement extended through a newfound energy that reached beyond from toes and fingertips and unblocked her already delicate lines. Her pantomime, her character, became vivid rather than textbook. I’ve been waiting for Park to surprise herself (and us) and here she demonstrated a new kind of abandon, of inflection, of fullness of body.

Well, she looked at me

And I, I could see

That before too long

I’d fall in love with her

She wouldn’t dance with another

Ooh, when I saw her standing there*

Throughout the ballet, Louvet and Park danced for each other and not for themselves (which had been a weakness for both to grow out of, I think). Park’s acting came from deep inside. From inside out for once, not demonstrated from without. During her mad scene, I simply put my notebook down.

Act 2 got off to a… start. Sylvia Saint-Martin clearly worked on controlling all the technical detail but danced as harshly as is her wont for now. The disconnect between her arabesque, torso, and abrupt arms, the way she rushes the music, the way her jumps travel but don’t really go anywhere…everything about her dance and stage presence just feels aggressive and demonstrative from start to stop. She finally put some biglyness into her last manège, but it was too late for me.

Well, my heart went « boom »

When I crossed that room

And I held her hand in mineOh we danced through the night

And we held each other tight*

There was a different kind of emotional violence to Germain Louvet’s first entrance, reacting to THIS Giselle. Along with the flowers, he carried a clear connection to the person from Act One onto the stage. You don’t always get the feeling that Giselle and Albrecht actually see each other from the backs of their heads, and here it happened. Both rivalled each other in equally feathery and tremulous beats. Their steps kept echoing each other’s. Park’s Giselle was readably trying to hold on to her memories, and moved her artistry beyond technique. This newfound intensity for her was what I’d long hoped for. I am still impressed by how visible she made Giselle’s internal struggle as the dark forces increasingly took control of her being and forced her to fade.

I left the theatre humming as if the thrum of a cello and the delicate lift of the harp were tapping on my shoulder.

Now I’ll never dance with another, Ooh.*

*The Beatles, “How Could I Dance With Another?” (1963)

Sae-Eun Park (Giselle) et Germain Louvet (Albrecht)

* *

Swan Lake, Sae-Un Park with Paul Marque on June 28th

However, this performance saw the ballerina go back into comfort mode.

However, this performance saw the ballerina go back into comfort mode.

In Act 1 Pablo Legasa, as the tutor Wolfgang aka Rothbart, instantly asserted his authority over Siegfried and the audience understood in a way that it hadn’t with Docquir whose presence didn’t still does not cross the footlights . Legasa’s tutor gleefully set up the about-to be-important crossbow as he slid it into Marque’s hands, just as he would later use that cape better than Batman. Most Rothbarts manipulate the Loïe Fuller outfit like a frenemy, at best.

The little dramatic nuances matter. Whereas Louvet’s Siegfried hadn’t really wanted to rock the boat much during Act 1 — so to be fair Docquir didn’t have that much to do — tonight Legasa repeatedly denied Paul Marque, whose Siegfried is more of a regular guy, any escape or release without express permission.

Paul Marque doesn’t possess the naturally elongated lines of Germain Louvet, but that isn’t a problem for me. Marque’s vibe feels more 19th century: dancing at its best: a restrained yet elevated 90 degrees back then was the equivalent of 180 now and every step he makes is as clearly outlined as if it popped out of an engraving. The way he worked up towards making the last arabesque in his solo arch and yearn gave us all we wanted as to insight into the internal trauma of the character.

In Act 2, Sae-Eun Park finally arrived to the delight of her fans. She gave a very traditional and accomplished classic rendering of Odette, replete with big open back, swanny boneless wings/arms, took her time with the music and became a beautiful abstract object in Siegfried’s arms. Her solo was perfectly executed. Could I ask for anything more? Maybe?

You have to make it work for you. O’Neill remained a woman, a princess trapped in some kind of clammy wetsuit and gummy gloves that covered her fingers. Park outlined and gave a by the book performance of the expected never having been a human swan. But at least now she dances from the inside out and her arms do fully engage in dialogue with her back.

I loved the way this Siegfried reacted to all the swans. “What? You mean there’s more of them?” Marque, as in Act One, then chiselled a beautifully uplifted variation that felt true to Nureyev’s vision in the way a synthesized centeredness (thesis) encounters and surmounts a myriad of unexpected changes in direction (antithesis). Very Hegelian, was Marque’s synthesis. Bravo, he made philosophical meanderings come alive with his body.

These lovers are lulled into the idea that escape is possible and will happen soon.

In Act 3, Legasa continues to lead the narrative. He is clearly whispering instructions into Odile’s earbud while also utilizing his cape and hands as if they were remote control.. For once Rothbart’s solo did not seem like a gratuitous interruptionsreplete with awkward landings. The pas de deux can in fact be a real pas de trois if that third wheel unspools his steps and stops and brings out the underlying waltzy rhythm of the music. Legassa tossed off those double tours with flippant ease and evil father-figure panache. Nureyev would have loved it.

Park’s Odile? Marque recognized his Odette instantly. Park did everything right but only seemed to come into her own in her solo (from where I was sitting). Even if her extended leg went up high and she spinned like a top, at the end of the pas de the audience didn’t roar.

“When Siegfried discovered he has both betrayed and been betrayed, Louvet, like a little boy, he wrapped his arms desperately tight around his mother.” Why did I write that in my notebook at the exact moment when I was watching Paul Marque in the same pantomime? I don’t quite remember, but I think it was because “mama” wasn’t what anything was about for him.

In the last Act, while Legasa acted up a storm, Marque remained nice and manly. The night before, Germain Louvet had really put all his energy into seeking Odette and fighting back against the forces of darkness. He really ran after what he wanted. Marque is maybe just not as wild by nature. Or maybe he just stayed in tune with Park? In Act 4, Park did fluttery. Lovely fluttery arms and tippy-toes that stayed on the music and worked for the audience. I observed but didn’t feel involved.

For me, only Pablo Legasa made me shiver during this Park/Marque Swan Lake. I found myself wondering what Park would have done IF a more passionate dancer like Legasa – as Louvet had been recently for her Giselle – had challenged her more. Now that I think back, Marque, too, had hit a high dramatic level when recently paired with Ould-Braham in Giselle. Maybe it’s time to end “ParkMarque.” I like them both more and more, just not together.

Le Lac des cygnes. Sae-Eun Park (Odette/Odile) et Paul Marque (Siegfried).

*

* *

Héloïse Bourdon: The Treasure that’s been hiding in plain sight.

You may say I’m a dreamer

But I’m not the only one*

Swan Lake, Héloïse Bourdon and Jerémy-Loup Quer, on July 12th

Swan Lake, Héloïse Bourdon and Jerémy-Loup Quer, on July 12th

Then on July 12th, something long anticipated didn’t happen. Again. As she had way back then on December 26th, 2022, Heloïse Bourdon gave yet another stellar performance as Odette/Odile in Le Lac des Cygnes. At the end, as the audience roared, so many of us expected the director to come out and finally promote Bourdon to étoile (star principal). Instead all we all got do was shuffle out quietly and once again go home to wash off what was left of our mascara.

If anyone managed to find the perfect balance between woman and swan this season, it was Bourdon. Even in the prologue, this princess showed us that she felt that danger prickling down the back of her neck just as an animal does.

As the curtain rises after this interlude, Jeremy-Loup Quer’s Siegfried puts his nightmare aside and is feeling just fine with his friends. He will later prove rather impervious to his mother’s admonitions and more boyishly cheered by her gift of the crossbow. Then, there was the moment where he looked intently at his baby throne only to turn his back on it in order to stare out of once of the the upstage window slits.

This Siegfried’s melancholic solo was infused by a kind of soft urgency, where the stops and starts really expressed a heart and mind unable to figure out which way to go. Touchingly, Bourdon would echo exactly this confused feeling in her solo in the Second Act, bringing to life the idea that Odette is both a product of Siegfried’s imagination and indeed a kindred soul.

As Wolfgang the Tutor, Enzo Saugar had made his entrance like a panther, a strong and dark-eyed presence with threateningly big hands. I instantly remembered his first splash on the stage as a very distinctive young dancer in Neumeier’s Songs of a Wayfarer at the Nureyev gala last year . Alas, as of now, Saugar continues think those eyes and those splayed fingers suffice. This works at first glance, but goes nowhere in terms of developing a coherent evening-long narrative. He just wasn’t reactive. He was performing for himself.

So thank goodness for Heloïse Bourdon. As Odette, she uses her fingers and wrists mightily as well, but with variety and thought. Hers was a woman and swan in equal and tortured measure. When she encounters Siegfried, he is clearly instantly delighted and she is clearly a woman trapped in a weird body who hestitanly wonders whether he could actually be her saviour.

Whereas Louvet’s Siegfried had seemed to say when the bevy of swans had filled the stage, “What? The world has always been full of swans?! This is like so unbelievable,” Quer seemed to be saying, as with the Princesses later: “Pleasure to meet you, but for me there is only one swan and I’ve already found her.”

I’d have to agree. Bourdon glowed from within without any fuss, and this was magnified by the unusual way she used her arms. Some dancers don’t connect their arms to their backs, which I hate. When dancers make their arms flow out from their backs this gives their movements that necessary juice. But here Bourdon’s arms had a specific energy that I’ve rarely seen. It flowed and contracted inward in waves from her fingers first and then pulled all the way back into her spine. I was convinced. That’s actually how you do feel and react when you are injured.

Throughout the evening, whether her swan was white or black, these two danced for each other, including not leaving the stage after a solo and staying focused for their partner from a downstage corner. Whether in Act Two or Four, each time Rothbart tried to rip her out of Siegfried’s arms via his spell, this couple really fought to hold onto each other. You could understand this prince’s bewilderment at a familiar/unfamiliar catch-me-if you-can Odile. (Perfectly executed, unbelievably chiselled extensions, fouettés, etcetera, blah blah, just promote her already).

Like Giselle, this Odette knew her hold on life was fading as the end of the last act approached. The energy now reversed and seemed to be pumping out from her back through her arms and dripping out of her hands and beyond her control. This Siegfried, like an Albrecht, like someone in a lifeboat, kept begging his beloved to hold fast.

The Paris Opera’s management may be blind, but the audience certainly wasn’t. I saw a lot of red eyes around me as we left the theatre in silence. Oh what the hell. As long as Heloïse Bourdon continues to get at least one chance to dance a leading role per run I can dream, can’t I? Next time, how about giving her a Giselle for once?

Imagine there’s no heaven

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us, only sky**John Lennon, “Imagine” (1971).

Le Lac des cygnes. Héloïse Bourdon (Odette/Odile) et Jeremy-Loup Quer (Siegfried).

Dans la lecture de Rudolf Noureev, souvent décrite comme « psychanalytique », le lac n’est qu’une vision dans l’esprit troublé du prince ; trouble, provoqué par le conflit oedipien que lui impose son précepteur (Wolfgang au premier acte et Rothbart aux trois suivants).

Dans la lecture de Rudolf Noureev, souvent décrite comme « psychanalytique », le lac n’est qu’une vision dans l’esprit troublé du prince ; trouble, provoqué par le conflit oedipien que lui impose son précepteur (Wolfgang au premier acte et Rothbart aux trois suivants).

Le Lac des Cygnes, Paris Opera Ballet, March 11, 2019

Le Lac des Cygnes, Paris Opera Ballet, March 11, 2019 Le Lac des cygnes. Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris. Mercredi 14 décembre 2016.

Le Lac des cygnes. Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris. Mercredi 14 décembre 2016. The basic story is so ridiculous even Freud would break out in giggles. A mama’s boy falls for a female impersonator really into feathers who goes by the moniker #QueenOfTheSwans. He digs her divine Virgin in White get-up but can’t stop making googly eyes at a sexy fashionista in black who turns out to be her -get this – Evil Twin. Then there’s the problem of their pimp. Since our hero has also demonstrated from the outset that he’s a limp noodle when it comes to standing up to father figures, he’ll…oh never mind. I mean, would you keep a straight face if late one night a middle-aged guy suddenly jumped out of the bushes, ripped open his Bat-cape, and exposed you to…his sequined green bodysuit?

The basic story is so ridiculous even Freud would break out in giggles. A mama’s boy falls for a female impersonator really into feathers who goes by the moniker #QueenOfTheSwans. He digs her divine Virgin in White get-up but can’t stop making googly eyes at a sexy fashionista in black who turns out to be her -get this – Evil Twin. Then there’s the problem of their pimp. Since our hero has also demonstrated from the outset that he’s a limp noodle when it comes to standing up to father figures, he’ll…oh never mind. I mean, would you keep a straight face if late one night a middle-aged guy suddenly jumped out of the bushes, ripped open his Bat-cape, and exposed you to…his sequined green bodysuit?

It’s time for the Prince’s birthday party. Guests who seem to have been called forth from the Habsburg empire – Hungary, Spain, Naples, Poland — perform provincial dances in his and our honor.

It’s time for the Prince’s birthday party. Guests who seem to have been called forth from the Habsburg empire – Hungary, Spain, Naples, Poland — perform provincial dances in his and our honor.