George Balanchine’s Theme and Variations, Mthuthuzeli November’s Rhapsodies, Christopher Wheeldon’s Corybantic Games.

George Balanchine’s Theme and Variations, Mthuthuzeli November’s Rhapsodies, Christopher Wheeldon’s Corybantic Games.

October 17th and 18th, 2025, at the Opéra Bastille in Paris.

This new season the triple bills are advertised under teaser catch-all titles that make no sense whatsoever. The one I’ve seen twice in a row is entitled “Racines” [aka “Roots”]. Now, as far as the Paris Opera Ballet goes, what do Balanchine, November (a newcomer), and Wheeldon have to do with our “roots?” Tchaikovsky, Gershwin, Bernstein? Well, if you are an American, the latter two just might work as far as your roots go.

I walked in — and alas left — the Opera Bastille both evenings still unable to find the answer. Came home rooted around the refrigerator, in search of comfort and inspiration. I know this sounds like what am I about to write will be pretty gnarly, but please bear with me.

Once I’m done, I’m going to finally look at the essays in the program book and see if that adds some enlightenment.

*

* *

Theme & Variations.

Zucchini Blossoms/ George Balanchine’s Theme and Variations (1947)

Have you ever planted zucchini in your garden? It just never stops sneakily extending its roots in all directions. By the end of the season you just cannot even look at even one more piece of your neighbor’s redundant zucchini bread. That’s Sleeping Beauty, tasty, but two long runs of it last season turned out to be more than filling.

Zucchini blossoms offer a delicate synecdoche for all that raw bounty. They are, in a sense, all the flavor concentrated into one juicy fried mouthful. Maybe this is one way to define how Theme and Variations distills Sleeping Beauty: the essence is there, minus the endless fairies.

Unfortunately, there are as many opinions out there about THE “authentic” way to dance Balanchine technique as there are recipes that do, or do not, include nutmeg. Ben Huys of THE Trusts (both Balanchine and Robbins!) was the invited coach. This ballet, despite its surprising construction – the ballerina barely gets to breathe during the first half and then mostly polonaises around for the rest – always turns out to be very tasty.

So let’s just enjoy the show and take a look at the dancers.

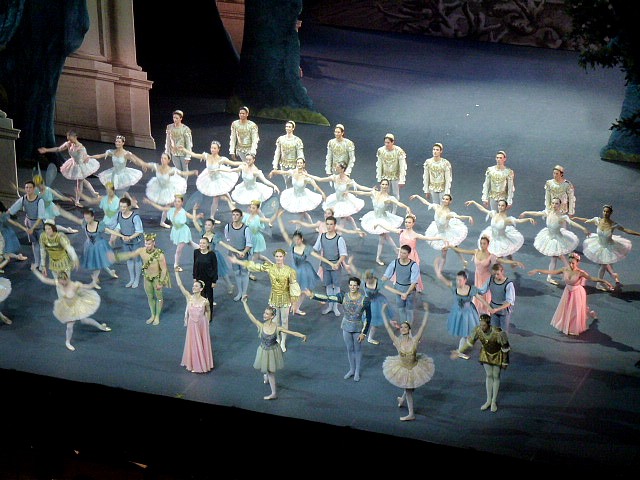

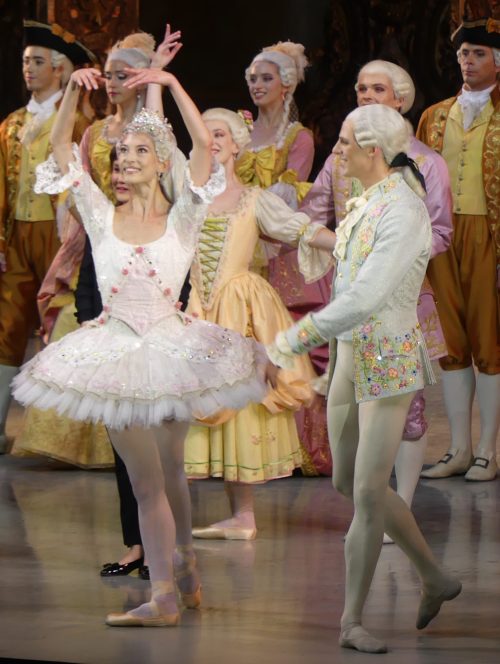

On October 17th, from the initial danced statement of the theme up to their deeply elegant réverances, both Bleuenn Battistoni and Thomas Docquir were still clearly inside their heads as Aurora and Désiré from last spring. And they continued to be that way, all the way through. But, as the last time, there was just 1% missing. A dash of pepper. Battistoni reiterated the unemphatic grace of her first act Aurora: all about just the right uplift and épaulements and un-showy but oh-so centered rock-solid balances. But this performance could also use just one more pinch of spice. Docquir, as he did last spring, concentrated on making his steps and jumps and batterie as scholastically perfect as possible. His performance wasn’t radiant. In princely roles, he seems to be fighting imposter syndrome. He rushed the music in partnering at times.

Honestly, this Theme was lovely, courtly, polished. The soft and precise landings into every pose at the end of a sequence literally pulled the audience in. I noticed that my neighbor kept leaning forward towards the stage each time, as if she had been swept up into 18th century courtesies, impelled to bow in return.

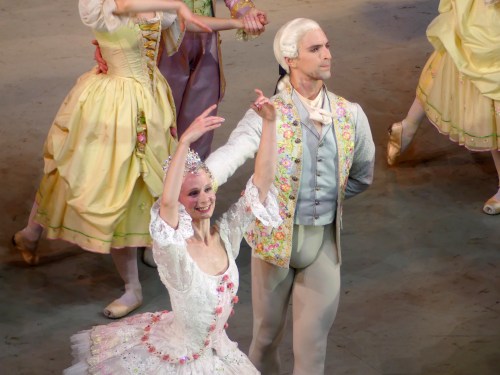

October 17th 2025. Bleuenn Battistoni & Thomas Docquir. Theme & Variations.

With Valentine Colasante and Paul Marque on October 18th, Theme felt looser and more fun. It was Beauty, but Act 3. Colasante luxuriated into the movements and teeny-weeny stretch-the-movement-out just enough beyond the axis to make a swish-swish seem new. She danced big, fearlessly, and playfully dared to hover a microsecond too long. Both dancers caressed the air and the floor. And there was something intriguing about the way Marque partnered: he seemed to catch her before the lifts, rather than on the way down, if that makes sense.

After the ballet, I thought about this very French concept of “la belle presentation.” Have you ever looked into a shop window in Paris where all the foodstuffs – from succulent to basic — are beautifully organized? Even bouquets of radishes are carefully placed in delicate patterns. Theme and Variations definitely suits our sense of l’art de vivre.

On both nights, I overheard complaints about the tiny corps on occasion not getting to their places and not lining up properly. Yes, yes, I did see it: one of the four girl soloists, and then especially when the male corps showed up. It’s not worth it to name names, as we have Giselle and a tour going on and are spread thin. Quite a few in the tutus and tights were newish to the stage. I find this critique particularly funny as Paris Opera Ballet is often accused of being too perfect from top to bottom.

As Balanchine would say, “who cares?”

*

* *

Rhapsodies. Magda Willi for Mthuthuzell November’s Rhapsodies.

Fennel and Endive /Mthuthuzeli November’s Rhapsodies (2024)

Who knows what to do with fennel or endives? Braise? Slice down in some direction and drench in lemon? No matter what, you have no answers. Maybe they just aren’t meant to be cooked.

Maybe Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue – by a composer who wrote pop music but wanted to be taken seriously – just isn’t meant to be used for a ballet?

Other choreographers have taken it on. In Paris, Odile Duboc did in 1999. It was insipid and has long gone into the dustbin.

Mthuthuzeli November’s take on the music has a lot more going for it. Or does it?

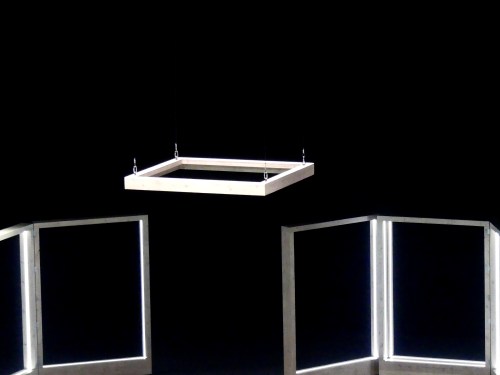

A clever set that leaves you puzzled, to start with. The outlines of wooden door frames are highlighted by led lights. The frames are attached to each other and can be pulled out like accordions and wheeled around or reshaped into one square outline as clouds of dried ice float by. I thought of Olafur Eliasson’s “Inside the Horizon,” that unfolding series of slivered reflections at the Louis Vuitton Foundation. I began to recall the many times Jean Cocteau made characters walk through mirrors in his films. My seatmate – after we made a pact that we would both not put our noses into the program beforehand – concentrated hard and said she saw people trying to step away from their cellphones. A French friend had seen French windows.

So the set gets you from the get-go, even if your mind drifts back to how many choreographers have used moving sets to incite and inspire movement since the beginning of time…

And does the dance get your attention? It’s perfectly watchable, nicely thought out.

On the 17th in the lead couple Celia Drouy, sensual and rounded, was the charming girl next door. I’d love to see her in Dances at a Gathering. It was odd then, late in the piece, when she shoved away her partner, the cooly intense Axel Ibot. It seemed to come out of nowhere.

October 17th 2025. Rhapsodies.

The dance? Watchable and performed with energetic commitment by all. The cast was filled with skilled soloists who are only occasionally ever cast in big roles, such as Ibot (eye-catching here and equally focused the next night when he rejoined the corps) or Fabien Révillion (a delightful Colas long ago and a wrenching Lensky recently). I often watch for Isaac Lopes Gomes, cleanly and powerfully performing no matter what line he’s stuck in. Daniel Stokes. Juliette Hilaire. Charlotte Ranson…

Ah yes the dance. Forgot that one. Weight down but pulled up. A repeated group movement of squats in second thump forward while swaying side to side à la les drinking buddies in Prodigal Son. Open your arms to the sun and close them at varied speeds. Embracing the sky is common to almost all local world dances as well as yoga. Push and pull. As a young woman once said to me after she tried a baguette for the first time and did not want to seem ignorant: “I wasn’t amazed, but it was soft, it was crunchy, it was warm! It was soft and crunchy! Wasn’t it supposed to be soft and crunchy?”

On the 18th I think another layer got added to Rhapsodies. Letizia Galloni was laid back/avid, out-of-here/imperious, chiseled/pliant. She projected a mysterious anguish and tension which made you notice from the start that she was indeed pushing back at her partner, Yvon Demol. Even when Galloni yields, she holds something back.

Letizia Galloni is another one of those soloists whose career has switched on and off and on. Talented and eye-catching from the time she graduated the POB school, she scored La Fille Mal Gardée during the Millepied era about ten years ago. Then she faded into herself. Then disappeared. (At least here in a national company, you can go into hibernation without being fired). But she popped up again last spring in Sleeping Beauty and offered the audience one of the loveliest Gold and Silvers I’ve seen in many a year: relaxed, imperious, generous, impeccable technically, with a sense of bounce and sweep that made us in the audience glad for her.

*

* *

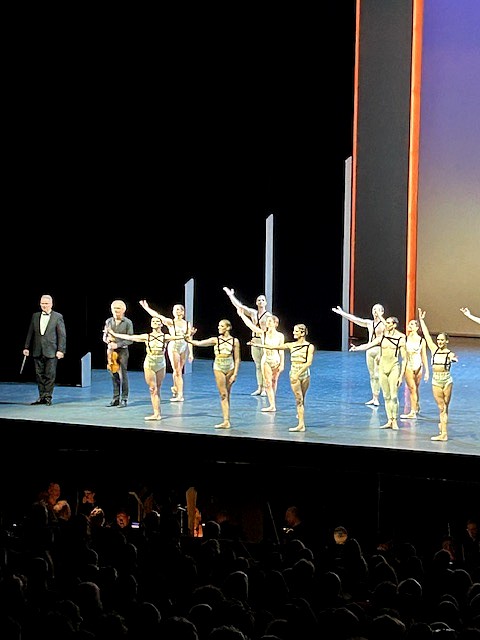

October 17th 2025. Corybantic Games.

Turnips/ Christopher Wheeldon’s Corybantic Games (2018)

Un “navet” aka turnip is the French way to say “that was a real dud.” I could have called this ballet a turkey, but we being very svelte and are only going to eat veggies today.

This thing, created for The Royal Ballet in 2018, has no structure (dramatic or balletic), no core, and dithers endlessly along. My seatmate on the 17th called it “soporific.” I thought of nastier words but simply nodded. I seriously considered skipping it on the 18th. Once was more than enough.

The pretty costumes are white with black ribbons crisscrossed across the torso that then dangle down from the shoulders. During the second night’s curtain calls, I tried to see if there was some sense to the danglers. Seems like the more of a soloist you are, the more ribbons.

The pretentious music is by Leonard Bernstein whenever he windily demands to be taken seriously. I’d call it Bride of Agon. The choreography, equally self-infatuated, proffers up innumerable quotes from just about every ballet that had an Antique World-y theme to the point that you could use it as a quiz: Note down the minute and the second where this choreographer directly cites Nijinsky, Nijinska, Robbins, Balanchine, Taylor. From Faun(s) to Apollo to Antique Elegies, this whole ballet felt like some snarky schoolboy’s inside joke. Flexed heels and upside-downsies and, as my seatmate noted, a lot of great final poses that turn out to be just a hook for more of the same. The Third Movement pas de deux ends with the guy hurling the girl up and into the wings (to be caught). Just where have I seen that one before?

It just goes on and on. I am too tired to describe it. Only a few days later I stare at my scribbled notes and all images of actual movement have faded. The steps from scene to scene – indeed within one — never get individuated. I’m looking at the cast list, filled with up-and-coming and cherished dancers and it’s painful. People tried to shine, gave it their all, but.

In the last scene, a soloist turns up (Valentina Colasante on the 17th and Roxane Stojanov on the 18th). Clearly, she is supposed to mean something, but what? Yes, I did know who the Corybantes were and that their earth mother is the fertility goddess Cybele (pretentious me) but what I didn’t see was one drop of wild ecstatic energy — not even once! — during these long minutes (37 minutes says the program, felt at least twenty minutes longer).

So now I’m looking at the program notes. Oh! Games is about Plato’s Symposium and polyamory! A less sexy or sensual ballet you will never find. No one connects. Ever. It turns out that in the fourth movement, if you look closely, the three couples are a straight, a male, and a lesbian one. Ooh! Did I look for boobies at all while three pairs of soloists in low light diddled around before settling into lovely enlaced poses on the downstage lip like teddy bears going to beddy? Seriously? As a female, I should note that women of any kind had no legal status or interest at all to Ancient Greek life or thought. Plato didn’t give a flying…hoot… about women, gay or straight. Why didn’t Wheeldon just make a dance about men being men who then tolerate a female diva who shows up for the grand finale? A fun fact is that Cybele’s male followers often castrated themselves at the apex of their delirium. Come to think about it, I don’t think that would make for a great ballet either.

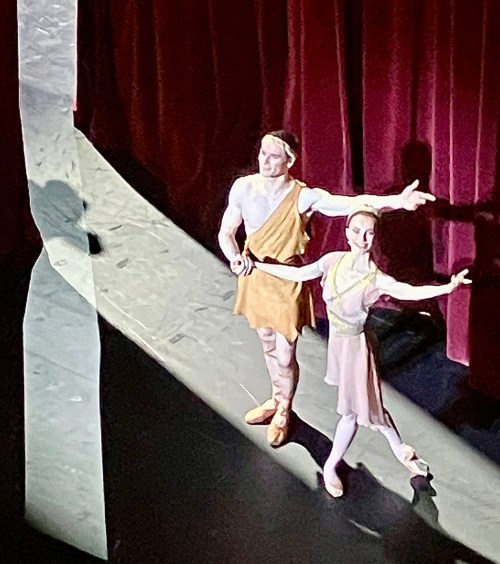

Bleuenn Battistoni & Roxane Stojanov, Corybantic Games.

As far as the title “Roots” goes, the program book insists that Wheeldon’s roots are in Greece. Seriously? He’s about as English as they come. As for Mthuthuzeli November, the program talks less about his native origins and much more about his discovery of ballet. This program should have been entitled « Apples and Oranges with a Dried-Out Raisin on The Side. »

Could someone please pass the salt?

Stagecraft

Stagecraft

James : représentation du 30 octobre 2024.

James : représentation du 30 octobre 2024.

Cléopold : représentation du 5 novembre 2024.

Cléopold : représentation du 5 novembre 2024.

Fenella : soirée du 13 novembre 2024

Fenella : soirée du 13 novembre 2024