Les Balletotos se sont cotisés pour voir trois distributions différentes du Mayerling de Sir Kenneth MacMillan. Tels des boas constrictors qui auraient mis du temps à digérer leur proie volumineuse, ils se résolvent enfin à vous en rendre compte. Fenella est enragée, Cléopold assommé et James… juste tombé sur la tête?

*

* *

James : représentation du 30 octobre 2024.

James : représentation du 30 octobre 2024.

J’ai trouvé la recette pour passer une bonne soirée à coup sûr : voir le spectacle à travers les yeux de quelqu’un d’autre. J’ai longtemps hésité à revoir Mayerling, dont j’avais fait une overdose lors de son entrée au répertoire de l’Opéra de Paris. Pour cette année, une revoyure serait le maximum. J’ai même failli revendre ma place, mais une charmante amie qui avait pourtant une journée bien chargée a insisté pour découvrir l’œuvre, et je ne pouvais pas la laisser en plan. Et me voilà arpentant tous les couloirs et escaliers de Garnier – et il y en a de lépreux – pour narrer les nombreuses péripéties de chaque acte, détailler les interactions entre les personnages, donner des pistes pour reconnaître les perruques, tenter de rabouter tout cela à la géopolitique de l’Empire austro-hongrois, avant qu’il soit temps de nous faufiler en troisièmes loges.

Et là, miracle, la magie du spectacle opère. À chaque instant, je vérifie que les épisodes annoncés (« tu vas voir, dans la scène du bal, Rodolphe danse, non pas avec son épouse, mais avec la sœur de celle-ci ! ») sont compréhensibles, et du coup, suis attentif au moindre détail (tiens, je ne souvenais pas ce qui déclenche cette entorse à l’étiquette : sa mère, déjà, lui manifeste une horrible froideur). C’est comme si l’œil brillant de ma voisine contaminait mon regard. De blasé, me voilà neuf.

Oh, tout n’est pas parfait. Les quatre zigues qui harcèlent le prince pour lui faire embrasser la cause de la Hongrie manquent de rudesse et ne dansent pas toujours ensemble (ils seront plus à leur aise à l’auberge au deuxième acte ; il s’agit de damoiseaux Busserolles, Lopes Gomes, Marylanowski et Simon).

Mathieu Ganio et Héloïse Bourdon. Répétition à l’amphithéâtre Olivier Messian. 12 octobre 2024.

Mais il y a Mathieu Ganio, dont on voit cette saison les derniers feux ; le danseur-acteur donne toute la palette de son art dans le rôle du prince Rodolphe. On voit à travers lui la morgue, la rage, les doutes, la névrose. À chaque pas de deux – et il y en a de nombreux – il adapte son style à sa partenaire et à la situation de cœur de son personnage : dragueur insolent avec la princesse Louise (Ambre Chiarcosso), il est las mais sensuel avec son ancien collage Marie Larisch (Naïs Duboscq), avant de se faire effrayant et glaçant de violence dédaigneuse avec son épouse Stéphanie (Inès McIntosh très touchante en fétu de paille). Approchant sa mère (Héloïse Bourdon, toute de grâce avec tout le monde et toute de glace avec lui), on le voir redevenir enfant. Au deuxième acte, lors de la scène de la taverne, il fait montre d’une élégance inentamée aussi bien pour son solo de caractère que lors du duo avec Mitzi Caspar (une Clara Mousseigne un poil trop élégante).

Alors que la névrose du prince progresse, Mary Vetsera prend son ascendant : Léonore Baulac incarne avec une crâne détermination le seul personnage qui dialogue d’égale à égal avec le prince ; le passage où elle inverse les rôles (Rodolphe avait terrorisé Stéphanie avec un pistolet, elle fait de même) scelle le pacte de mort qui occupera le dernier acte. Dans le rôle de Bratfisch, serviteur fidèle de Rodolphe, Jack Gasztowtt est presque trop grand et élégant, mais il habite avec précision sa partition, et avec sensibilité son rôle d’amuseur (2e acte) qu’on ne regarde plus (3e acte).

*

* *

Cléopold : représentation du 5 novembre 2024.

Cléopold : représentation du 5 novembre 2024.

Sans doute parce que je n’avais pas comme l’heureux James pour sa soirée une charmante voisine à mes côtés, je n’ai pas eu d’épiphanie face au mastodonte Mayerling. Le ballet apparait toujours avec ses mêmes gros défauts, sa myriade de personnages accessoires, notamment féminins, le tout encore aggravé par cette spécialité de l’Opéra de distribuer les rôles plus selon la hiérarchie de la compagnie que selon la maturité physique des interprètes. C’est ainsi que le 5 novembre, dans son pas de deux du « dos à dos » avec Rodolphe, Célia Drouy, par ailleurs fine interprète, a l’air d’être la petite sœur de son partenaire et non sa mère. Sylvia Saint-Martin tire son épingle du jeu en Marie Larisch. Sa pointe de sécheresse donne à l’intrigante comtesse une image vipérine qui s’accorde avec le premier pas de deux qu’elle a avec le prince héritier tout en enroulements-déroulements – notamment le double tour en l’air achevé en une attitude enserrant le partenaire- . Marine Ganio est quant à elle très touchante ; aussi bien dans son solo de jeune mariée où, malgré les signes contraires donnés pendant le bal, elle espère encore trouver dans le prince héritier un mari, que dans le pas de deux « monstre à deux têtes » de la chambre nuptiale.

Marine Ganio (Sophie), Francesco Mura (Bratfisch) et (? ahhh La confusion des personnages multiples et vides)

On l’aura compris, on se raccroche au pas de deux comme un marin naufragé aux planches éparses du navire englouti. MacMillan reste un maître incontesté du genre. Et qu’importe si chacun des personnages féminins qu’il dépeint à part peut-être Mary Vetsera se voit refuser toute progression dramatique. Chacune d’entre elles reste l’allégorie d’un type de relation avec le prince héritier.

C’est pourquoi on ne voit guère en Mayerling qu’une tentative ratée de surenchérir sur le succès de Manon, créé quatre ans auparavant. La scène la plus emblématique de cet échec est à ce titre celle de la taverne qui tente de transposer, de manière pataude, l’acte « chez Madame » de Manon. En effet, on y trouve une myriade de prostituées qui se dandinent et se chamaillent. Un personnage masculin secondaire exécute une variation aussi bouffonne qu’acrobatique (Francesco Mura donne à ce numéro de Bratfisch une jolie bravura, entre relâché –les roulis d’épaules- et énergie coups de fouet des sauts). Un personnage secondaire féminin danse une variation sensuelle (Clara Mousseigne atteint les critères techniques du rôle sans parvenir à donner corps à sa Mizzi Caspar). Un quatuor de messieurs fait des grands jetés dans tous les sens (Les Hongrois de carton-pâte qui jusque-là ressemblaient plutôt à des polichinelles sortant de leur boite – MacMillan aurait mieux fait de ne pas aborder le volet politique si c’était pour le traiter de cette manière). La police vient enfin gâcher la fête.

Seulement voilà, dans Manon, la scène chez Madame vient faire avancer l’action : des Grieux, voit sa fiancée volage revenir à lui. Lescaut, qui favorise ce retour de flamme après avoir été la cause même du départ de l’héroïne, perd la vie. Manon est arrêtée et va être déportée en Louisiane. Dans Mayerling, la scène n’apporte pas grand-chose au développement de l’action. Que nous importe que Rodolphe propose le suicide à Mizzi Caspar quand la chorégraphie ne nous a suggéré aucune vraie intimité, même sensuelle, entre les deux personnages. Peut-être aurait-il dû proposer le marché à Bratfisch. Cela aurait, peut-être, donné une raison d’exister à ce personnage accessoire se résumant à ses deux variations.

Invariablement, cette scène inutile émousse suffisamment mon attention pour me trouver indifférent à un moment pivot du ballet, celui du salon de la Baronne Vetsera où, durant un tirage de cartes truqué, Marie Larisch finit de tourner la tête à la jeune écervelée Mary Vetsera – le rôle féminin principal- qui, depuis le début du ballet, ne faisait que passer.

Il faut donc attendre la moitié de la soirée pour rentrer dans le vif du sujet et c’est sans compter encore deux autres scènes parfaitement inutiles : la réception au palais de la Hofburg où on nous inflige tous les proches et illégitimes de la famille impériale (en amant de Sissi, Pablo Legasa est grossièrement sous employé) et la scène à la campagne (beaucoup de décors et de figurations pour un coup de fusil).

C’est un peu comme si MacMillan, qui avait su condenser la Manon de l’abbé Prévost, n’avait pas su sélectionner les épisodes les plus significatifs qui ont conduit le prince au tombeau. Un ballet n’est pas un livre d’Histoire et multiplier les notes de bas de page ne fait assurément pas une bonne histoire.

Hohyun Kang et Paul Marque (Mary et Rodolphe).

Mais venons-en –enfin !- aux personnages principaux. En Rodolphe, Paul Marque, assez compact physiquement, torturé et introverti, nous crée des frayeurs au début du ballet. Il cherche ses pieds lors de sa première variation (ses chevilles tremblent sur les pirouettes et même en échappés). Le pas de deux avec la sœur de Stéphanie (Luna Peigné) est un peu périlleux avec des décentrés ratés. On craint un peu pour la jeune danseuse. Cela s’améliore par la suite. Paul Marque joue très bien la maladresse et l’inconfort. Il semble déplacé au milieu de tous ces ors et ces fastes. Il est même touchant dans la scène de chasse, avalé qu’il est par son lourd manteau et sa toque. Il est aussi un morphinomane poignant mais convainc moins en Hamlet sur Danube, dans ses confrontations avec le crâne.

Pour le drame, on se repose alors sur Hohyun Kang qui, assez charmante et lumineuse dans ses premières scènes de presque figuration, se mue assez vite en liane à l’élasticité toxique. Sa Mary est un petit animal qui ronronne et griffe tout à tour. A l’acte 3, la scène de la mort, avec ses portés-synthèses de tous les autres pas de deux avec les autres interprètes féminines, est d’un effet monstrueux.

Mary-Hohyun accrédite l’idée d’un vrai sacrifice consenti. Elle semble rester complètement dans l’exaltation jubilatoire du suicide romantique. Je préfère la version où la jeune fille recule au dernier moment et est emportée par la folie de Rodolphe qu’elle a activement encouragée. Le choix présenté par Kang et Marque est cependant très valide.

Mais Dieu qu’il faut patienter pour en arriver là ; et que de fois on a cru sombrer dans les bras de Morphée avant ce dénouement.

Hoyun Kang (Mary), Paul Marque (Rodolphe) et Silvia Saint-Martin (Marie Larisch).

*

* *

Fenella : soirée du 13 novembre 2024

Fenella : soirée du 13 novembre 2024

SHOOT!

Mayerling by Sir Kenneth MacMillan, Paris Opera Ballet at the Palais Garnier, November 13th, 2024.

Even if you put a gun to my head, I will never ever go see this ballet again.

The potential dramatic arc keeps shooting itself in the foot as hordes of pointless people keep disturbing the crime scene. This cacophony of characters only serves to distract and, worse, confuse an audience unversed in the minutiae of minor late 19th century Central European history.

During the early scene at a ball, once again I just kept trying to guess who’s who, as did the two women sitting in front of me who were leaning in and actively chatting to each other. “Archduchess Gisela,” seriously? Who? Who cares? Who even cared back then? The character is a non-character, a company member who was just wasted playing a titular extra. (At least 18 roles have names in the cast list).

So there. Now back to the topic at hand. What I saw. And it didn’t start well.

Then, after having been absolutely gobsmaked by an Emperor Franz Joseph doing heavy squats in second when he was supposed to be leading a Viennese waltz with upright elegance, I started to sink down in my seat. I will not out the very young dancer who perpetrated this assault on the waltz as either he was not, or was seriously badly, coached. Clearly, more attention was paid to his wig and costume. If you are going to be so historically correct that you give specific names to minor characters…maybe you should pay attention to little details such as how a waltz is properly danced?

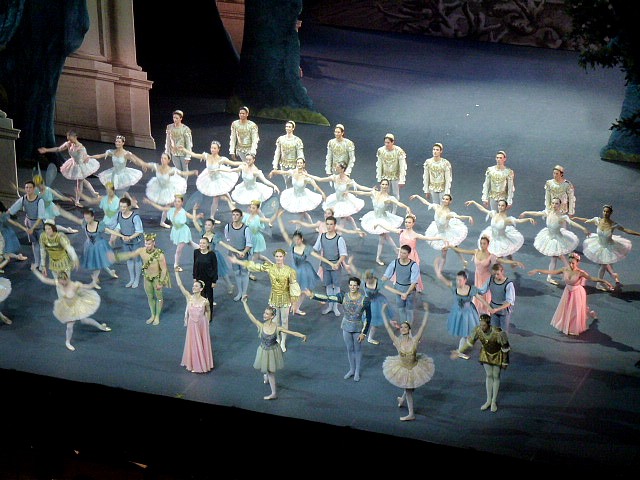

Curtain calls. The too many characters

Oh yes. The leads.

Germain Louvet as Crown Prince Rudolph nailed it. He’s grown into his talent. He’s gone from being a youthfully pretty star into this manfully expressive artist, all without losing a sliver of his lines and elan. He’s really in the zone right now and, despite the fact that I think this ballet is a total waste, he made it work for us in the audience. From his first entrance as Rudolf, Louvet set out a complicated but readable persona: already anguished, brusque; very proper manners if required but clearly not a fool, not naive (and not as mad as others, such as his mother, assume he is).

As his mother, Empress Elizabeth, Camille Bon did impose a calm presence. You could tell she was his mother from scene to scene, no matter what the hat or hair. In their only intimate encounter, the one in her bedroom, there was no doubt that this woman hated to be touched by her son. The little kiss goodbye on the forehead never fails to pin down what kind of mother the dancer has shaped. Alas, later on, when Elizabeth dances pointlessly with a lover who suddenly pops up in the deserted ballroom, neither radiated charisma (not to mention desire). Why not just ERASE Sissi’s pointless boyfriend “Colonel Bay Middleton” Cast member #9? I wanted to remove him at gunpoint. No one in the audience has ever been able to tell who the hell he is supposed to be.

As Rudolph’s battered bride, Countess Stephanie, Inès McIntosh proved naively helpless, but not hopeless and definitely not a ninny. You started to cheer for her: if only her new husband could tell that she’s just as melancholic as he is! Just not as crazy. And if only her new husband could see that her body does match his in lines and energy. Both Louvet and McIntosh have an unassuming way of lifting and extending their legs that makes the high lines seem natural. Neither of the two kicks or flings their legs about needlessly. Their extensions soar up softly and take time to soak in the music. They’d make a nice couple, given a chance.

Heloïse Bourdon, whom I had once seen playing Rudolfs’s mother with cold fire, was unrecognizable (in the best way) here as Countess Larisch. Healthy, sane, pragmatic – you almost could imagine that the Habsburg Empire wouldn’t have fallen if she’d been Franz Joseph’s Pompadour rather than Rudolph’s enabler. Actually, her countess seemed more wry and disabused than enabling. Yes, a Pompadour: elegant, smart, knows someone will always hate her for where she comes from.

Mayerling. Curtain Call.

By first intermission, I was already thinking about the busy 1953 Warner Brother’s cartoon Duck Amuck, where Bugs Bunny progressively erases Daffy Duck. And now, please, for Act Two:

CUT the tavern scene with Mizzi Caspar, which provides zero dramatic purpose or emotional payoff. I mean, this endless scene finally fizzles out when Mizzi — whom we have not seen before …and will never see again – gets taken home by another man who probably has a name in the program? He might be #10 or #11, who cares? Waving papers around (ooh, plot clue) is something to be saved for a close-up in a BBC miniseries.

As Mizzi, however, Marine Ganio infused her persona with the voluptuous Viennese charm of what they call “Mädls:” « Girlies » with hearts of brass.

Some can even manage, like Ganio, to be one of the boys when dancing to Liszt’s Devil’s Waltz with four pointless Hungarians. [Don’t even ask me about the score. I want to burn it]. OK, maybe do not FULLY ERASE the tavern scene entirely but please: just EDIT OUT these “Hungarian” Jack In The Boxes from the entire ballet. I was rather annoyed that James did not find them rough and rustic enough. Le Sigh, they are supposed to be noblemen aka elegantly sinuous whisperers, not tough guys.

Louvet’s Rudoph was the happiest and least tormented when dancing with Marine Ganio’s Mizzi, even when he was pulling her in too manaically. Their yearning to stretch matched, their arms – even when in tight couronnes — matched. There was a story ready to be told here, but that would have been a different ballet.

Please CUT the ennnndless scene of the Habsburg Fireworks and thereby CUT the out-of-place diva impersonating “Katharina Schratt”, Franz Joseph’s actress mistress, as she sings to boring effect to live piano accompaniment. And CRUMPLE UP AND THROW OUT: The Hunt, oh god please. OK, Rudolph killing someone, by accident or on purpose, is based on a true story. As the guy already is a drug and sex addict, syphilitic, and just plain nuts, does this excuse to make a prop gun go pop…add anything to the narrative?

Most of all: CUT CUT CUT Bratfisch, the loyal coachman, OR at least please give him enough to do to make him identifiable! As is, he is a 5th Jack In The Box, but a lonely one who dances alone. As this character is 8th out of 18 in the playbill you might not notice that he was the first guy you saw on the snowy stage of Act One Scene One. Antoine Kirscher, eh? Didn’t he also get cast as the naughty coachman (aka the guy with a horsewhip) in Neumeier’s La Dame aux camellias? Here Kirscher couldn’t quite make as much of a sassy statement in the endless tavern scene, hampered by the fact you had no idea who he was supposed to be. Now seriously dated Groucho Marx references don’t help the younger ones in the audience. Nor could you tell that the sad guy in the last scene in the churchyard was someone you’d seen before. Even with two solos, it’s a non-role and no dancer, none, has been given enough to chew on to really make it work.

Oh, and by the way, one of the many pretty girls who’d been popping in and out for at least an act and a half then turns out to be the starring female role: Mary Vetsera, the last of Rudoph’s mistresses, the only one who turns out willing to die with/for him. Bluenn Battistoni. Clearly not naïve: she’s a girl of our time who has seen too much perversion on the internet that she thinks doing “x”(spellcheck just censored me) on a first date is normal. Battistoni’s Mary was clearly not a drama queen with death wish either. Just a girl…and perhaps Louvet’s Rudolph was a bit too careful with his ballerina during the final flippy- flappy too-much is not enough MacMillan partnering.

Honestly, by the time the action got around to Mary, at some point after the tavern or the hunt, I must have been weirdly smiling: I was now thinking about that 1952 cartoon “Rabbit Seasoning” where Bugs asks his nemesis whether Elmer Fudd should shoot him now or shoot him later. If this ballet ever shows up in the Paris Opéra repertory again, I swear I shall scream, like Daffy Duck, “I demand that you shoot me now!”

Don Quichotte on March 27th

Don Quichotte on March 27th

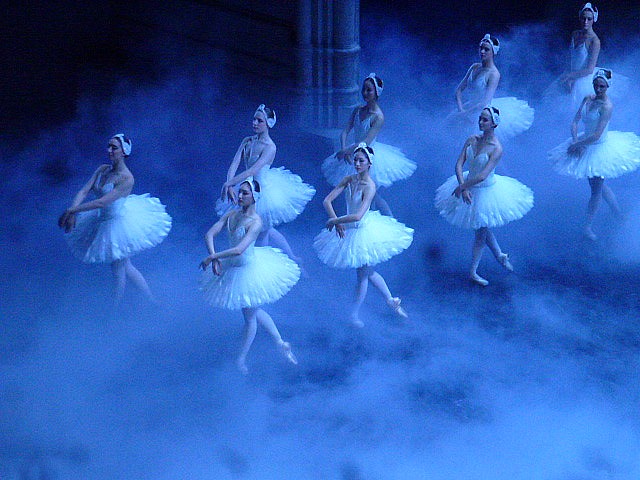

Le Lac des cygnes on June 27th

Le Lac des cygnes on June 27th

During Giselle, what I’ve been looking for finally happened. Before my eyes Sae-Un Park evolved from being a dutiful baby ballerina into a mature artist. And her partner, Germain Louvet (again!) whom I’d often found to be a bit “lite” as far as drama with another goes, came to play a real part in this awakening.

During Giselle, what I’ve been looking for finally happened. Before my eyes Sae-Un Park evolved from being a dutiful baby ballerina into a mature artist. And her partner, Germain Louvet (again!) whom I’d often found to be a bit “lite” as far as drama with another goes, came to play a real part in this awakening.

However, this performance saw the ballerina go back into comfort mode.

However, this performance saw the ballerina go back into comfort mode.

Swan Lake, Héloïse Bourdon and Jerémy-Loup Quer, on July 12th

Swan Lake, Héloïse Bourdon and Jerémy-Loup Quer, on July 12th