In-Between The Beauties

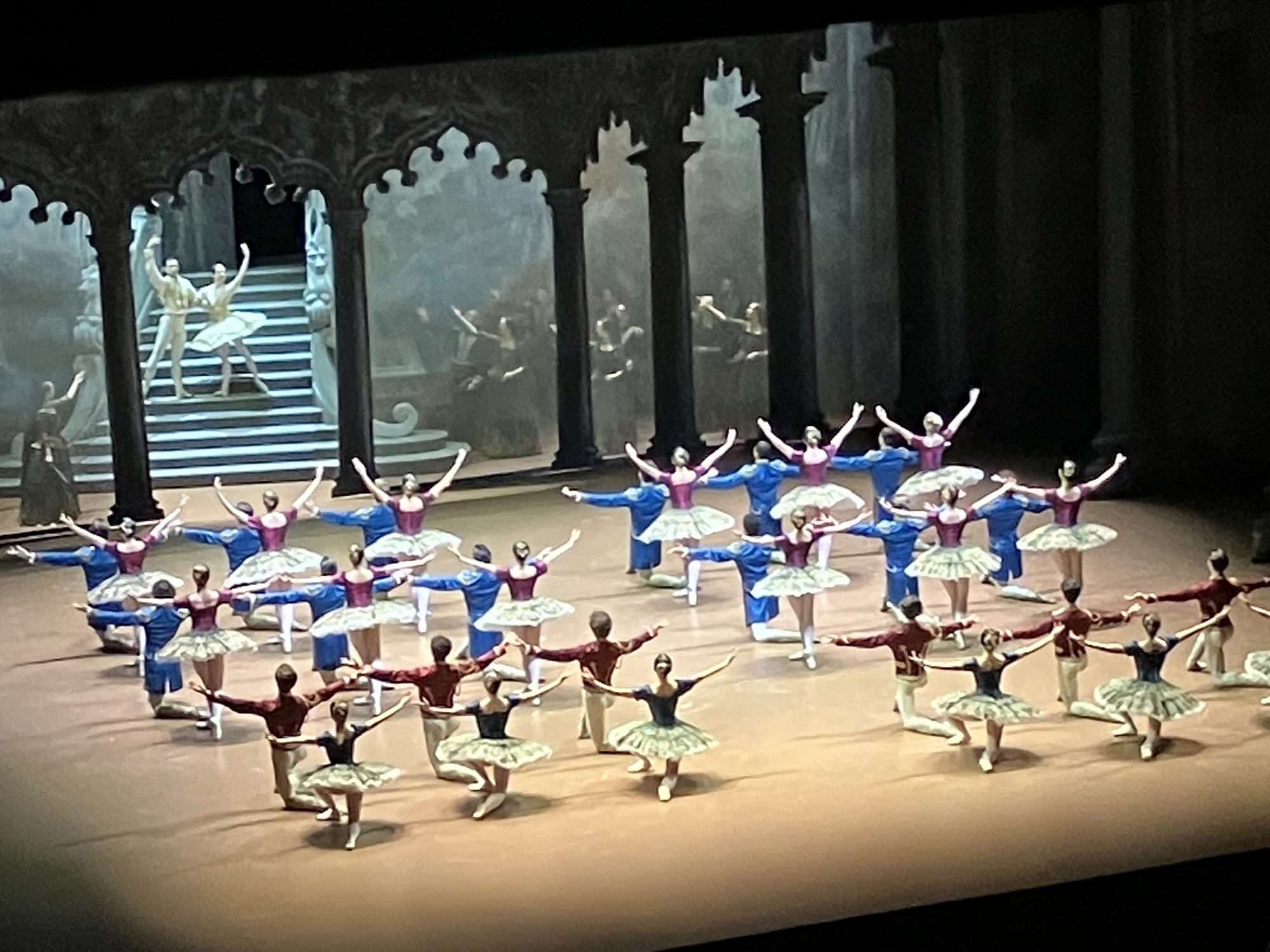

Sylvia : ensemble.

Manuel Legris’s Sylvia, Palais Garnier, May 8th & 9th

Sandwiched in there, between Belles, we were treated to a short run of a revival/re-do of the ballet Sylvia, which had disappeared from the Paris repertoire.

I had never seen Darsonval’s 1979 version, alas. I will always regret how the Paris Opera then also deprogrammed the one I knew: John Neumeier’s late 1990’s visually stunning version but esoteric re-interpretation of the story. It did take a while to figure out that Eros and Orion had been conflated into the same dancer by Neumeier, yet the choreographer’s vivid sense stagecraft worked for me emotionally. All the better that Neumeier’s original naïve shepherd, Aminta/Manuel Legris himself, decided to try to piece together a new version that reached back to the ballet’s classic roots.

It was particularly odd to see most of the Sleeping Beauty casts now let loose/working overtime on this new production. While the dancers gave it their all, quite a few of the mythical beings were sabotaged by a production that included some very distracting costumes and wigs.

The Goddess Diana sports a basketweave ‘80’s Sheila Easton mohawk that would make any dancer look camp. In the role, a rather ferocious Roxane Stojanov held her head up high and ignored it, while the next evening a tepid Silvia Saint-Martin disappeared underneath the headgear to the point I had forgotten about her by the time she reappeared on stage near the conclusion. The interactions between Diana and Endymion make no sense whatsoever, particularly when you are at the top of the house and cannot see what is happening on the little raised platform at the back of the stage. Imagine trying to follow the plot when you can only see a bit of someone’s body wiggling, but without a head. Note to designers: go sit up at the top of the house and do some simple geometric calculations of vectors, please.

To add to audience discomfort (hilarity?) with the staging at some point Eros, the God of Love, will abruptly rip open the raggedy cloak he’d been disguised in (don’t ask) in order to flash his now simply gold-lamé-jockstrap-clad physique. On the 9th, Jack Gasztowtt managed to negotiate this awkward situation with dignity. On the 8th, having already gotten mega-entangled in his outerwear just prior to the reveal, Guillaume Diop didn’t. Seriously cringey.

There are many more confusing elements to this version, including the strong presence of characters simply identified as “A Faun” (Francesco Mura both nights) and “A Nymph” (a very liquid Inès MacIntosh on the 8thand a floaty Marine Ganio on the 9th). But what’s with the Phrygian bonnets paired with Austrian dirndls? The Flames of Paris meet the Sound of Music on an Aegean cruise?

In Act 3, some characters seem to wear Covid masks. So please keep the choreography, but definitely junk these costumes!

Despite these oddities, dancers were having serious fun with it, as if they had been released from their solemn vow to Petipa while serving Beauty.

On the 8th of May, Germain Louvet’s fleet of foot and faithful shepherd Aminta charmed us. His solo directed towards Diana’s shrine touched in how grounded and focused it was. His Sylvia, Amandine Albisson, back after a long break, seemed more earthbound and more statuesque than I’d ever seen her, only really finding release from gravity when she had to throw herself into and out from a man’s arms. But when Albisson does, gravity has no rules. Usually you use the term “partnering” to refer to the man, but I always have the feeling that she is more than their match. When I watch Albisson abandon all fear I often think back to Martha Swope’s famous photograph of Balanchine’s utterly confident cat Mourka as she flies in the air. When it’s Albisson, everything gravity-defying, up to and including a torch lift, feels liberatingly feline rather than showy or scary.

Here the hunter Orion is less from Ovid and more of a debauched pirate straight out of Le Corsaire. On the 8th, Marc Moreau at first moved with soft intention, clearly more of a suitor than a rapist where Sylvia was concerned. You felt kind of sorry for him. His switch to brutality made sense: being unloved is bad enough for a guy, being humiliated by a girl in front of his minions would make any gang leader lash out.

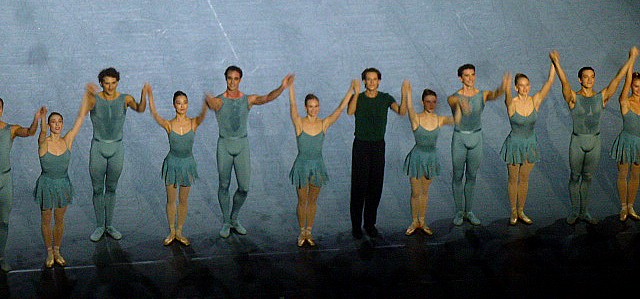

Marc Moreau (Orion), Amandine Albisson (Sylvia) and Germain Louvet (Aminta)

On the 9th, I had to rub my eyes. Bleuenn Battistoni – that too demure Beauty – provided the relaxed and flowing and poignant princess I had hoped to see way back in March. Nothing dutiful here. Already in the first tableau, without doing anything obviously catchy, her serene and more assertive feminine authority insured that the audience could immediately tell she was the real heroine – an eye-catching gazelle. Maybe Beauty is just too much of a monument for a young dancer? Inhibiting? Ironically, at the end of the season, I would see Albisson let loose as Beauty. The tables will have turned.

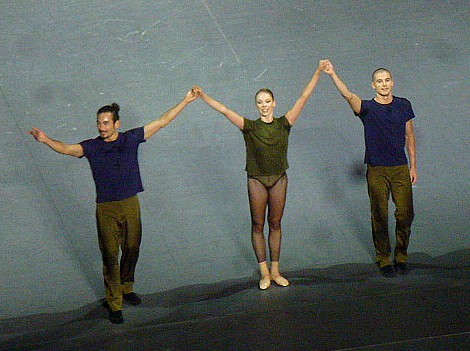

I was drawn to Paul Marque’s melancholy and yearning shepherd Aminta. At a certain point, Sylvia will be prodded by Diana to shoot her suitor. Albisson did. Here Battistoni (and who in any case would obey Saint-Martin’s dry Diana?) clearly does by accident, which made the story juicier. Battistoni’s persona was vulnerable, you stopped looking at the “steps” even during the later Pizzicati solo, which she tossed off with teasing and pearly lightness. Everything I had hoped for in Battistoni’s Beauty showed up here.

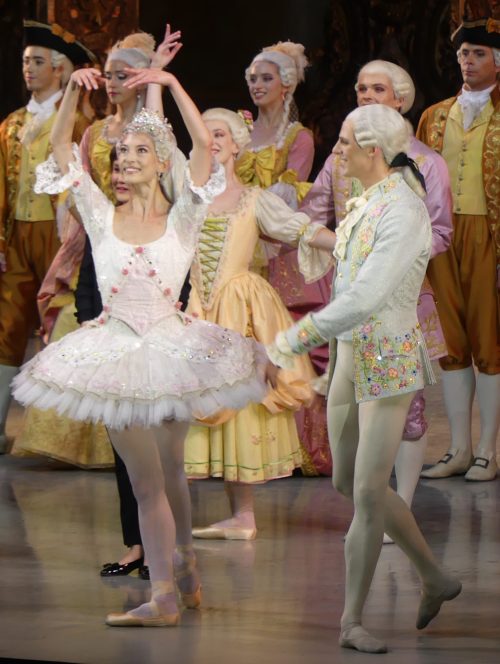

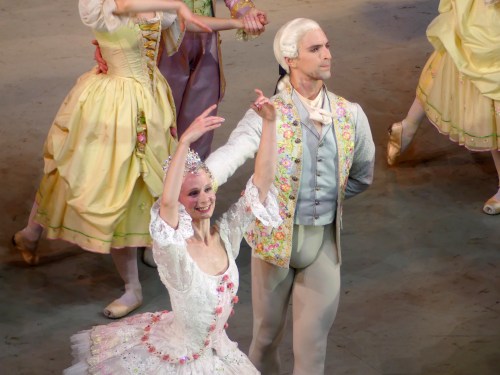

Sylvia : Paul Marque et Bleuenn Battistoni

*

* *

The Belles Are Ringing

La Belle au Bois Dormant’s second series. Opera Bastille, June 27th,July 6th and 7th.

Guillaume Diop et Amandine Albisson (Désiré et Aurore le 7 juillet).

And then, boom, Albisson full out in Sleeping Beauty on July 7th. As fleet of foot as I knew her to be, neither allegory nor myth but a real and embodied character. Whereas she had seemed a bit too regal as Sylvia, here came the nymph. Delicate and gracious in the way she accepted the compliments of all of her suitors, Albisson created a still space around her whence she then began to enchant her princes. She looked soundless.

Guillaume Diop, who had proven a bit green and unsettled earlier this series, woke up his feet, leaned into his Second Act solo as he hadn’t before – a thinking presence, as someone remarked to me – and then went on to be galvanized by his partner and freed by the music.

Perhaps Diop, like everyone else on the stage, was breathing a sigh of relief. For this second series of Beauties in June/July, the brilliant and reactive conductor Sora Elisabeth Lee replaced the insufferable Vello Pähn. During the entire first series in March and April, this Pähn conducted as slowly and gummily if he were asleep, or hated ballet, or just wanted to drag it out so the stagehands got overtime. With Sora Elisabeth Lee, here the music danced with the dancers and elated all of us. During the entire second series, Bluebirds were loftier, dryads were more fleet-footed. Puss and Boots had more punch and musical humor. Sora Elisabeth Lee gave the dancers what they needed: energy, punchlines, real rhythm. This was Tchaikovsky.

So this second series was a dream.

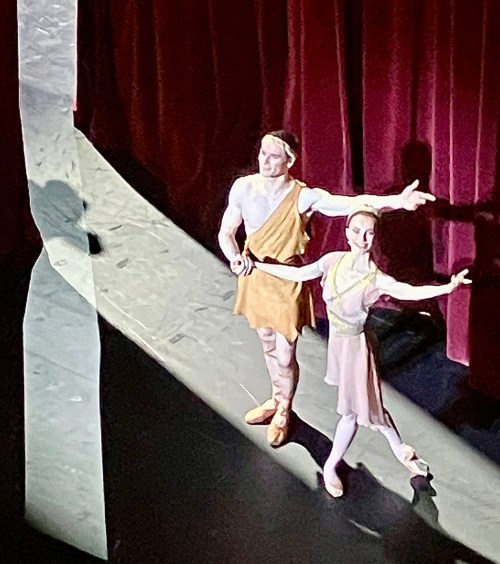

On July 6th, Germain Louvet proved that he has grown into believing he can see himself as a prince. I say this because I was long perturbed by what he said as a young man in his autobiography (written before you should really be writing an autobiography). An assertive prince, a bit tough and perfectly cool with his status as Act Two starts. And then he began unfurling his solo, telling his story to the heavens. His arms had purpose, his hands yearned. And when he saw his Beauty, Hannah O’Neill, it was an OMG moment.

As it had been destined to be. O’Neill’s coltish and gracious and sleek, sweetly composed and well-mannered maiden from Act One was now definitely a damsel in need of a knight in shining armor. She was his dream, no question. She began her Second Act solo as if she were literally pushing clinging ivy aside, her arms moving slowly and filling into spaces at the end of each phrase. No wonder that Louvet’s prince became increasingly nervous seconds later while trying to find his girl in among the sleepers. You could feel his tension. “Are they all dead? Was the Lilac fairy just fooling with me?” And, oh, Act Three. The way he presented his belle, the way they danced for each other.

Hannah O’Neill (Aurore) et Germain Louvet (Désiré)

But of all the Beauties, I will never forget Leonore Baulac’s carefree and technically spot-on interpretation, maybe because I just can’t find a way to describe this June 27th performance in words. Fabulous gargouillades? The way she made micro-second connections with all four of her suitors (and seemed to prefer the one in red)? The way everything was there but nothing was forced? The endless craft you need to create the illusion of non-stop spontaneity? The way Marc Moreau just suited her? Those supported penchées and lean backs in the Dream Scene as one of the most perfect distillations of call and response I have ever seen?

Both Baulac and Moreau sharply etched their movements but always made them light and rounded and gracious. Phrases were extended into the music and you could almost hear whispered words as they floated in the air. They parallelled each other in complicity and attack to the point that the first part of the final pas de deux already felt as invigorating as a coda.

Léonore Baulac et Marc Moreau (Aurore et Désiré).

You can never get enough of real beauty. Let’s hope 2025’s Paris fall season will be as rich in delight.

Stagecraft

Stagecraft

Paquita (Deldevez-Minkus / Pierre Lacotte d’après Joseph Mazilier – Marius Petipa). Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris. Représentations des 18, 23 décembre 2024 et du 1er janvier 2025.

Paquita (Deldevez-Minkus / Pierre Lacotte d’après Joseph Mazilier – Marius Petipa). Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris. Représentations des 18, 23 décembre 2024 et du 1er janvier 2025.